A Little More than Gruel

Food

in the Victorian Workhouse.

Please,

sir, I want some more.

Those words, the words of Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist, are amongst the most infamous in literature. They were spoken to the master of a fictional workhouse, where the poor young boy Oliver, and his fellows, were being slowly starved on a diet consisting of 'three small bowlfuls of oatmeal gruel per day, with an onion twice a week and a roll on Sunday.'

As a writer of dark, Victorian fiction, workhouses feature prominently in my work. It would be surprising if they did not, since, even as the most prosperous nation on earth at the time, somewhere between a quarter and a third of the population of Britain passed through the workhouse system at some point in their lives. So what was the reality of the workhouse in terms of diet? Was it really as bad as Dickens portrayed?

The short answer, in very general terms anyway, is, no, although gruel – a mixture of oatmeal (or oatmeal and flour) and water – did feature. After the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, workhouses were subject to the general control of the specially appointed Poor Law Commissioners. These quickly issued a set of six sample dietary tables to the individual Boards of Guardians, who then used these as the basis for the particular diet in their own workhouses. Any variations were subject to the agreement of the Commissioners.

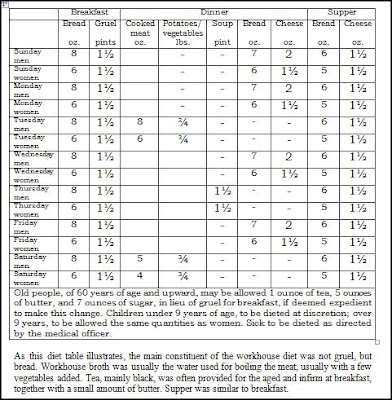

An example of an adult daily diet from the mid-nineteenth century is as follows:

As this diet table illustrates, the main constituent of the workhouse diet was not gruel, but bread. Workhouse broth was usually the water used for boiling the meat, usually with a few vegetables added. Tea, mainly black, was often provided for the aged and infirm at breakfast, together with a small amount of butter. Supper was similar to breakfast.

A basic principle underpinning the Poor Laws was that of ‘less eligibility’. I make detailed reference to it in my novel, The Eighth Circle of Hell. In other words, to discourage what might be perceived as ‘idleness’, conditions inside the workhouses had to be worse than those of the meanest labourers in the ‘outside World’. Unfortunately, this was sometimes used as a pretext for providing food made from cheap, poor quality ingredients, or for short rations.

By the 1890s, the fixed-ration dietary system was coming under particular scrutiny. By this time, most of the workhouse inmates tended to be the elderly or sick, and often found the coarse food difficult to eat. Bread in particular was being thrown away in vast quantities, since the regulations required that each inmate had to be given their prescribed serving, regardless of whether they wanted it or not. By the end of that decade, new regulations allowed workhouses to compile their own weekly menus from a range of about fifty dishes or ‘rations’. An official workhouse cookery book was compiled by the National Training School of Cookery with recipes such as batter pudding, bread pudding, seed cake, dumplings, fruit pudding, pasties, potato pie, rice pudding, shepherd's pie, haricot soup, lentil soup, pea soup, and of course...gruel.

A basic principle underpinning the Poor Laws was that of ‘less eligibility’. I make detailed reference to it in my novel, The Eighth Circle of Hell. In other words, to discourage what might be perceived as ‘idleness’, conditions inside the workhouses had to be worse than those of the meanest labourers in the ‘outside World’. Unfortunately, this was sometimes used as a pretext for providing food made from cheap, poor quality ingredients, or for short rations.

Workhouse inmates eating their meals in typically regimented rows.

By the 1890s, the fixed-ration dietary system was coming under particular scrutiny. By this time, most of the workhouse inmates tended to be the elderly or sick, and often found the coarse food difficult to eat. Bread in particular was being thrown away in vast quantities, since the regulations required that each inmate had to be given their prescribed serving, regardless of whether they wanted it or not. By the end of that decade, new regulations allowed workhouses to compile their own weekly menus from a range of about fifty dishes or ‘rations’. An official workhouse cookery book was compiled by the National Training School of Cookery with recipes such as batter pudding, bread pudding, seed cake, dumplings, fruit pudding, pasties, potato pie, rice pudding, shepherd's pie, haricot soup, lentil soup, pea soup, and of course...gruel.

Thanks for stopping by to share your food for thought, Gary!

You can find Gary here:

No comments:

Post a Comment